At the intersection of green hydrogen and social justice, the Hyphen project in Namibia represents one of Africa's most ambitious sustainable development initiatives. This large-scale green hydrogen project promises to transform both the energy landscape and local communities – but it doesn’t come without particular reflections to be made, especially with emerging studies that show the tendency to neglect sociopolitical considerations and prioritise donor interests. It's precisely this complexity that drew Marlene Merchert, a second-year MPhil Development Studies student and 2024 Ignacio Ellacuría Grant recipient, to examine the project through an energy justice lens.

Her academic journey was shaped by diverse experiences. In Germany, Marlene transitioned from business management in sales and consulting, and working for an IT company, to studying sustainable management while working as a freelance photographer. Ultimately, she realised that research was her path to asking the right questions, developing transdisciplinary approaches, and serving local interests.

It was a lecturer, who Marlene had approached almost by chance, who suggested that she should consider applying to Oxford after reading her paper on climate pricing. During the application process, Marlene recalls writing in her journal, "I feel like I'm going crazy applying to such an institution!" And even after being admitted, she didn't have an easy start: “Development Studies is completely different than what I had imagined. I struggled in the first and second terms: I thought I was not going to be able to pass because I didn’t have a background in the subject.”

At the intersection of green hydrogen and social justice, the Hyphen project in Namibia represents one of Africa's most ambitious sustainable development initiatives. This large-scale green hydrogen project promises to transform both the energy landscape and local communities – but it doesn’t come without particular reflections to be made, especially with emerging studies that show the tendency to neglect sociopolitical considerations and prioritise donor interests. It's precisely this complexity that drew Marlene Merchert, a second-year MPhil Development Studies student and 2024 Ignacio Ellacuría Grant recipient, to examine the project through an energy justice lens.

Her academic journey was shaped by diverse experiences. In Germany, Marlene transitioned from business management in sales and consulting, and working for an IT company, to studying sustainable management while working as a freelance photographer. Ultimately, she realised that research was her path to asking the right questions, developing transdisciplinary approaches, and serving local interests.

It was a lecturer, who Marlene had approached almost by chance, who suggested that she should consider applying to Oxford after reading her paper on climate pricing. During the application process, Marlene recalls writing in her journal, "I feel like I'm going crazy applying to such an institution!" And even after being admitted, she didn't have an easy start: “Development Studies is completely different than what I had imagined. I struggled in the first and second terms: I thought I was not going to be able to pass because I didn’t have a background in the subject.”

Was it the theoretical heaviness?

Heavily theoretical, yes. A lot of philosophy and anthropology, and a completely different way of thinking and seeing the world than I was used to. I came in with a very economic mindset, viewing development simply as economic growth, optimising welfare... So, at first, the more critical perspective in Development Studies felt like a very abstract way of seeing the world. But throughout the degree, I started to understand the benefits of these approaches. I felt like I could really combine theories and practices.

And how did you combine the two as you were designing your research? How did you approach transdisciplinarity and local sensitivity?

First, I find it important to understand the difference between interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. The former takes different disciplines together and draws on them but doesn’t necessarily synthesise them in a combined framework. Transdisciplinarity on the other hand does - and that's what I try to achieve in my research. I connect literature on just transitions, energy and environmental justice with systems thinking to develop a more holistic approach.

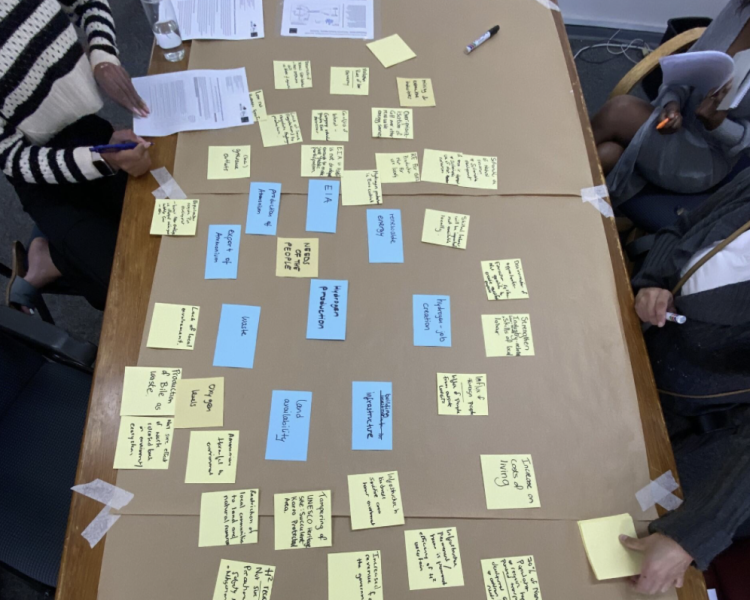

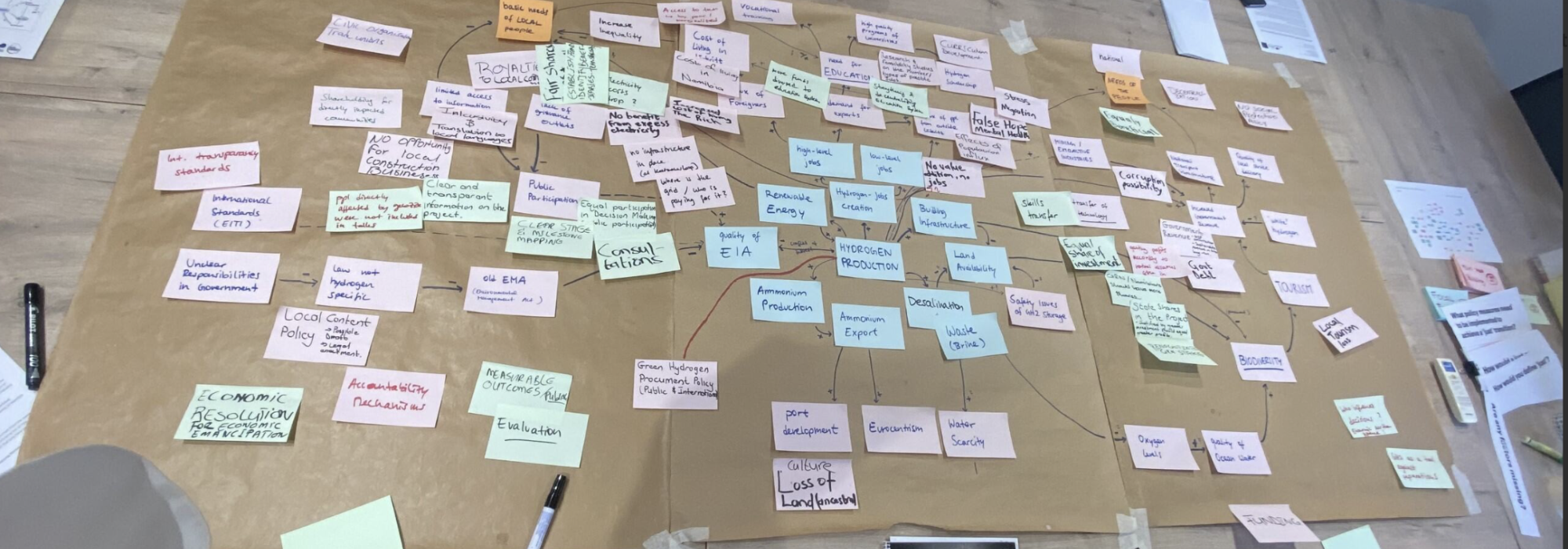

Second, I aimed to design a locally sensitive approach by adopting a participatory approach whenever possible, and including a broad range of stakeholders: non-academic, politicians, civil servants, people from industry and civil societies, traditional authorities, and local communities. I used participatory systems mapping, which involves getting a bunch of people around the table, to discuss and visualise connections using post-it notes. I wanted to see stakeholders not as research subjects, but rather as collaborators in the research.

Another way of designing locally sensitive research lies in the question that you’re asking. A lot of questions are rooted in academic interest: we have this theory, and we want to develop it. Research should not just serve academic debates but also address locally relevant concerns.

Now that you’ve done your fieldwork, and are progressing into your degree, how do you think academia can be in service of communities?

I love this question, because it touches on something I often critique in Development Studies. At times, academia can feel like an ivory tower, drive solely by academic interests. But can research be relevant? I think it absolutely can - and should be. We need to ask questions that matter to the people on the ground. Before setting up my research, for example, I spoke with Namibian activists to understand what issues they found important and what questions they believed needed asking.

Another challenge is how we communicate our findings. The way we speak in academia, and how we publish, makes much of our work inaccessible. Coming from a different discipline myself, I felt like I had to learn a new way of thinking and writing. I understand there might be a need for a particular language for an academic listener, but we should also think about publishing things for our local stakeholders in a more accessible format, and actively reach out to share our findings.

It forces you to be more genuine and real in your research as well. Oftentimes, because academia incentivises you to publish so much, you’re inclined to develop some interpretations that might be a little bit removed from what is actually going on. I think that, by committing yourself to make your findings accessible to your stakeholders, you’re forced to be grounded in reality.

Now that you’ve done your fieldwork, and are progressing into your degree, how do you think academia can be in service of communities?

I love this question, because it touches on something I often critique in Development Studies. At times, academia can feel like an ivory tower, drive solely by academic interests. But can research be relevant? I think it absolutely can - and should be. We need to ask questions that matter to the people on the ground. Before setting up my research, for example, I spoke with Namibian activists to understand what issues they found important and what questions they believed needed asking.

Another challenge is how we communicate our findings. The way we speak in academia, and how we publish, makes much of our work inaccessible. Coming from a different discipline myself, I felt like I had to learn a new way of thinking and writing. I understand there might be a need for a particular language for an academic listener, but we should also think about publishing things for our local stakeholders in a more accessible format, and actively reach out to share our findings.

It forces you to be more genuine and real in your research as well. Oftentimes, because academia incentivises you to publish so much, you’re inclined to develop some interpretations that might be a little bit removed from what is actually going on. I think that, by committing yourself to make your findings accessible to your stakeholders, you’re forced to be grounded in reality.